Exploring The Balance Between Hormones, Caffeine

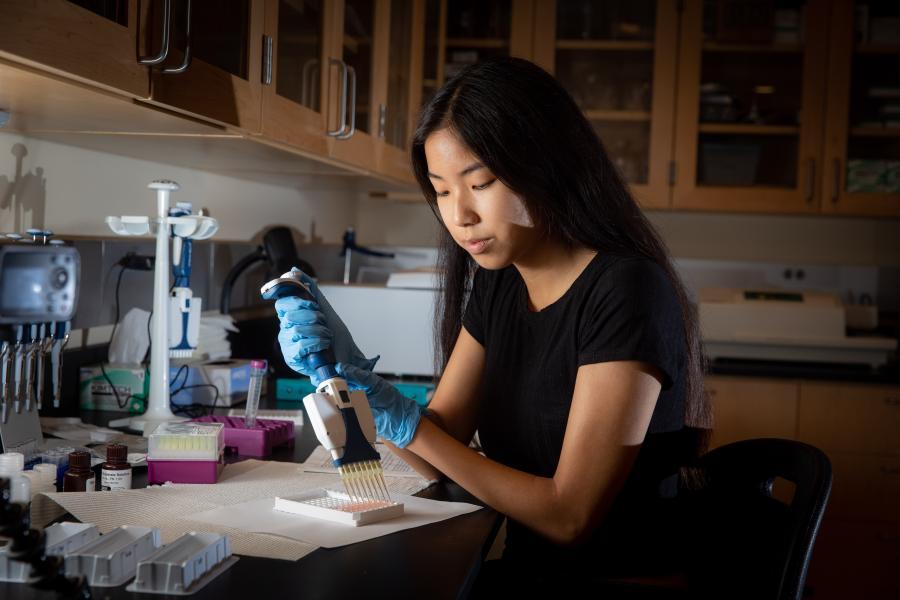

“I rarely drink coffee,” says Tiffany Gong ’23, a behavioral neuroscience student at Westmont, who is the subject and the researcher examining the impact of acute caffeine on cortisol and melatonin levels.

Gong, whose roommate strategically places a piece of duct tape over Keurig coffee pods to hide their caffeine content, records her salivary cortisol and melatonin levels six times a day.

“That’s an important part of the study because we can monitor the cortisol-melatonin cycles when she gets the acute caffeine and the days when she doesn’t and analyze what the caffeine did to disrupt the pattern or cycle of activity,” says Ronald See, Westmont professor of psychology and neuroscience.

“These two key hormones, cortisol and melatonin, show opposing circadian rhythms in terms of their circulating levels. We predict that acute caffeine in a non-tolerant subject will alter the relative ratios of these two hormones. We are also assessing working memory and sleep patterns over time.”

Cortisol levels are usually the highest in the morning and steadily decrease throughout the day, while melatonin levels begin to ratchet up in the evening.

Each morning, Gong drinks a cup of Pete’s House Blend Coffee, either with 100 milligrams of caffeine or with zero. She also compares the effect on her working memory through standardized tests. “They show pictures, and you’re supposed to click one and a previous one that showed up, like a picture of cheese, a baseball or a pencil, and it analyzes my results,” she says. “We anticipate that the caffeine improves working memory,” Gong says. “And I wanted to see whether acute caffeine would also impact my sleep that same night.”

“Tiffany is not a heavy caffeine user, so she may see an immediate and temporary effect in disrupting the ratio of those two hormones, cortisol and melatonin,” See says. “I’m interested in how the cortisol-melatonin fluctuates.”

A few years ago, See and another student researcher measured both hormones while the student shifted her sleep patterns. “Interestingly, the melatonin levels remained stable, but the cortisol began shifting, so the ratio between the two altered over time,” he says. “That result got us interested in the interaction between cortisol and melatonin, typically not studied together because they’re released by different parts of the nervous system. Their functions differ in many respects, but researchers are beginning to recognize their potential interaction.”

See and Gong have found some surprising effects of caffeine in their initial analyses, with both cortisol and melatonin levels substantially increasing with repeated caffeine drinking, but only when measured at 24 hours after coffee consumption.” Such changes may relate to the initial phases of tolerance to caffeine.